There is a growing list of experiments that I am eager to dive into in the studio at Dartmouth Avenue. For now, I envision small models and installations:

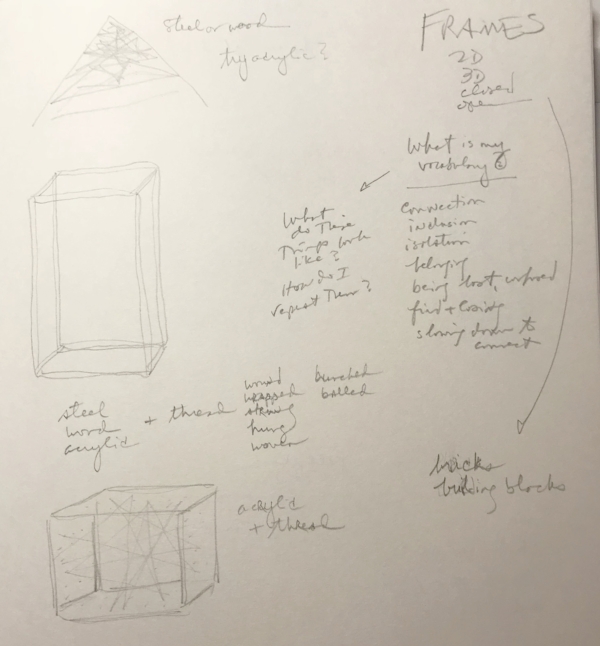

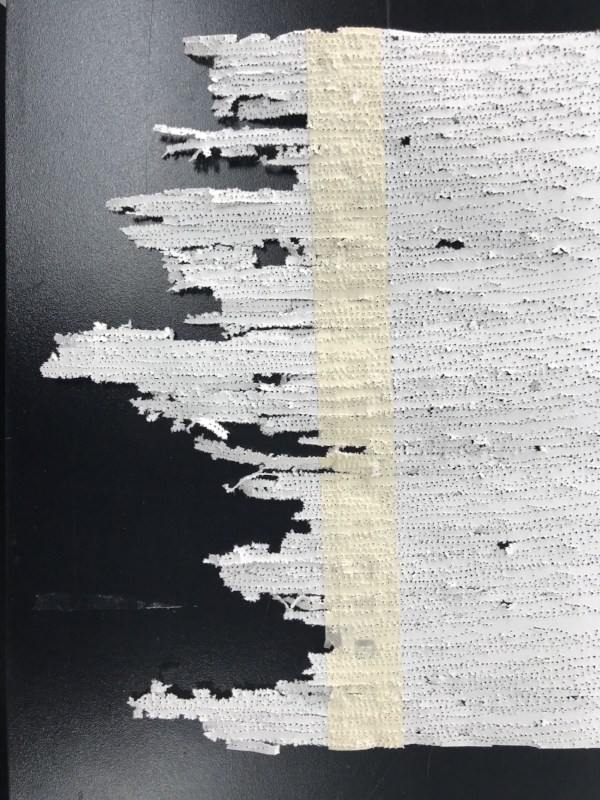

:: materials that read ephemeral, impermanent, vulnerable, friendly, human, warm, communicative, inviting (I have no idea how or what these involve, only the ideas at this point)

:: paper casts of small objects that have personal meaning

:: rubbings/frottage of surfaces and objects that are associated with home, place, belonging

:: combinations of objects that I associate with my father—the tools and materials he used in his work

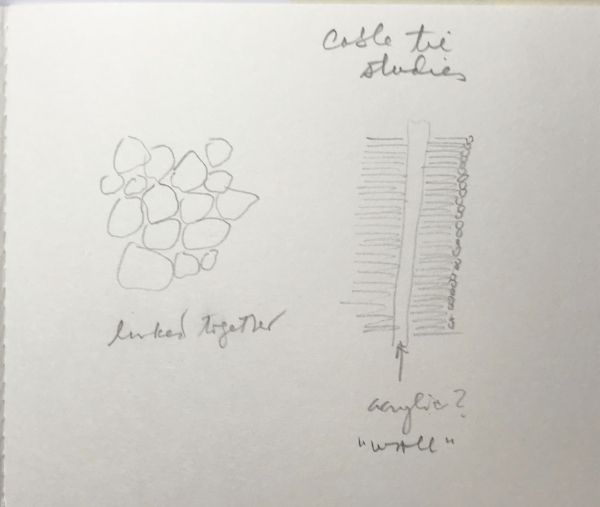

:: playing with the relationships between and among objects

:: how to suspend, support, connect things—invent and build my own systems, frames and supports

:: invented maps—drawn directly onto wall, layered in space, suggesting not only place and location but also layers of meaning

:: installations that inhabit and occupy my space

When we return after the Christmas break, these are some possibilities for re-entering my studio practice.

![Spike Island. (2017) [Instagram] 25 September 2017. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BZdjT6fjcGI/?taken-by=spikeisland (Accessed: 21 October 2017).](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52c54d77e4b073b4a439b935/1513010494746-5SKSK5WM1F32PFR4QGYQ/Kim+Yong+Ik+installing+at+SI.jpg)